Stage 24 – Russia: Siberia To Saint Petersburg

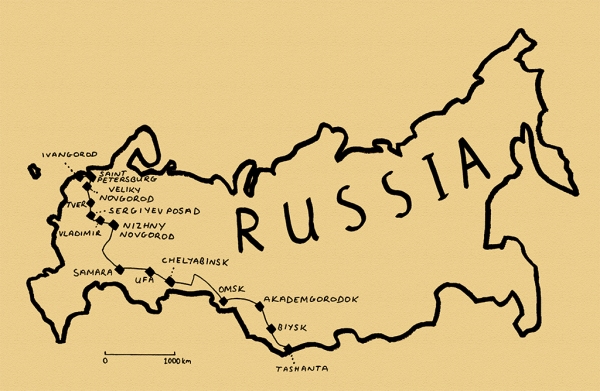

On this six thousand kilometre journey from the rugged mountains of western Mongolia to the Baltic Sea, I would pass straight through the very heart of Russia: into the centre of southern Siberia, over the Ural Mountains, along the Volga and through the most ancient heartland of the country to cities dating from a time when Russia was a far, far smaller entity. The trip would consist of a harsh and at times terrifying drive over several weeks through the onset of the infamous Russian winter, interspersed with the warmth and good company of the Russian people whom I would meet and stay with. As I slowly made my way ever westward, I would at once be effectively travelling backwards in time through Russian history, but at the same time would begin to see something less welcome come across the country; namely the increasing influence of more western values of commerce and consumerism replacing the wildness and rugged beauty of the east. Nevertheless, this winter crossing of a considerable slice of Russia would provide me with a greater understanding of the country’s historical and cultural roots than perhaps any other.

It’s the 23rd November 2010 and late in the day on by the time I clear the Russian border post at Tashanta and make my way to the district capital of Kosh Agach. The temperature is around -20ºC and falling, and after having dinner and filling the truck up with fuel I decide to continue driving, descending the glorious, winding Chuya Highway. Despite icy conditions and darkness and in full knowledge of the stunning mountain scenery which lurks in the dark, I continue driving cautiously through the night without stopping and by dawn I am in the snow-covered but comparatively warm lowlands of Siberia, reaching the small city of Biysk by mid-morning. After weeks of travel in Mongolia, my sudden arrival into the familiarity of urban Russia is something of a culture-shock, though a positive one, for it marks an end to the fear of becoming stranded in the trackless, snow-covered wilderness of Mongolia.

Biysk is a pleasant backwater, an eighteenth century trading post typical of the small Siberian cities which found themselves off the Trans-Siberian mainline when it was completed at the turn of the twentieth century. Time here appears to have moved more slowly than in the dynamic cities on the rail and road-conduits to the north, and there are plenty of examples of Tsarist-era buildings; timeworn structures of decorative whitewashed brickwork or of pastel coloured wooden panelling. Some, such as the City Library appear to be on the verge of collapse, but the city manages to retain a fairly dignified air nevertheless.

After two nights in Biysk I move north towards Novosibirsk, en route encountering the dangerous driving conditions which would underscore my journey all the way to the Baltic. It is in this early winter season that Siberian weather may be particularly unstable as weather systems clash from both north and south, bringing wild swings in temperature. I briefly encounter a phenomenon known as freezing rain: supercooled droplets of liquid water which freeze immediately upon impacting a surface; within minutes my windscreen becomes a sheet of solid ice.

I stop in the city of Akademgorodok, a suburb of Novosibirsk, location of Novosibirsk State University and the educational and scientific capital of Siberia. Rather than being an intriguing, previously classified Soviet research centre as I had perhaps imagined, Akademgorodok is little more than a large university campus, but my hosts would make my stay extremely memorable. They are Ilyas, a Kazakh from Almaty; Ivan, a local of Novosibirsk and his girlfriend Sasha who comes from the Commander Islands, the last of the Aleutians and surely one of the most remote places in all of Russia, lying well off the eastern coast of Kamchatka.

I am invited into the spacious apartment of my three student hosts and am immediately treated to a tea ceremony by Ilyas. Taking its roots in the Taoist-influenced cultures of China and east-Asia, the tea ceremony is a ritualised preparation and presentation of tea designed to bring out the best flavour of green tea and although certainly not native to Russia or Siberia, there are undertones of the New Age spiritualism which has a nascent following in the post-Soviet world. My three hosts are in fact members of the Tea Club, a social club based somewhat around tea ceremonies, and I am very glad to be invited to one of their meetings in central Novosibirsk one evening. This takes place in a dedicated cultural venue, where I form one of my fondest memories of Russia and Russian people. A small circle of friends gather, mostly academics and artists, bringing musical instruments and relaxing on cushions in a large open room. Tea is made ceremoniously and music played; the atmosphere is totally unpretentious, welcoming and relaxed, and I am infused with a very natural feeling of heightened awareness, something I have hardly felt before. It’s more refined and wholesome than typical western social activities which almost always revolve around drinking alcohol, and a perfect antidote to the stereotypical views of Russians being invariably heavy drinkers. I imagine that most people in the room refrain from drinking alcohol altogether. The music is earthy, imperfect and soulful, played at a volume which does not stifle conversation, and occasional mistakes are laughed off or ignored. Performers are not trying to prove themselves or fit into any pre-described social movement; it is simple, joyful socialisation of a kind which I have only ever experienced in Russia.

I’m sad to have to leave my hosts in Akademgorodok, but I am constantly hurried by the impending depths of winter which could leave me stranded (due to diesel fuel waxing, leaving the truck unusable). I drive west through the night on the M51, the western part of the Trans-Siberian Highway which crosses the snow-covered clearings and patches of now bare birch forest of southern Siberia, to the city of Omsk. Omsk lies on the Irtysh River which here is almost frozen solid and is Siberia’s second city, once briefly acting as the capital of the Provisional All-Russian Government, a final attempt to counter Bolshevism in the chaos of the Russian Civil War. During the Second World War, Omsk (after Samara) was prepared to become the Russian capital in the event of a German occupation of Moscow. Despite these brushes with greatness, Omsk has long-lived in the shadow of Novosibirsk and remains a city of very modest attractions. Temperatures of -25ºC don’t deter some of the locals from drinking vodka at tables outside the market, but I prefer to wait for warmer temperatures, and foolishly set off at midnight, westwards towards Chelyabinsk.

A couple of hours into the journey, out in the endless Siberian plains as I am driving along a nearly empty road at perhaps sixty kilometres per hour, the rear of the truck suddenly slides gently to one side, then immediately pirouettes 180º. In the moments that I am travelling backwards I anticipate disaster, but I merely leave the road and sink with a gentle impact into a snow-drift a few metres below the elevated road surface, without any damage at all. Every car which subsequently passes offers assistance, another admirable trait of Russian people, and after little more than an hour a large truck finally arrives which has the power to pull me back up onto the road. No money is asked for; I am merely wished luck in my onward journey. At this point I realise that the sudden increase in temperature to just above freezing has made the road surface a polished ice-rink on which I can barely even stand still without sliding. My summer-rated tyres have almost no grip whatsoever on such a surface.

With great caution and the truck now engaged in four-wheel drive, I resume my journey. The road is rough in places, coated in ice pounded into washboard-like ruts by heavy trucks. Through the day the temperature drops which has the advantage of reducing the amount of dirty brown slush being thrown out by vehicles. I detour via Tyumen through beautiful pine forests, avoiding a section of the M51 which crosses what is now the northern tip of Kazakhstan, rejoining it in Kurgan after dark where I encounter and the very first ripples of the Urals and yet more treacherous driving conditions; the roads are regularly lined by wrecked lorries which have spun off into the thick Siberian snow. At around 01:00 I finally reach Chelyabinsk, at -26ºC. In my state of hyper-awareness following spinning-off the road, I have driven twenty hours non-stop, my personal endurance record.

I’m hosted in Chelyabinsk by the Mayarov Family in their large lakeside house. The Mayarov’s are a good example of ‘Old Money’ in modern Russia, living in a self-built house with a front door like a bank vault and a heated underground garage. The welcome is typically Russian however, with long meals in the family kitchen, great home cooked food and only a little vodka. Chelyabinsk is a large industrial city typical of the Ural region to which industry was evacuated and subsequently developed to counter the threat of a Nazi invasion of western Russia, and I spend five days in the city relaxing and making friends before continuing my journey west.

West of Chelyabinsk is the infamous M5 Highway which winds over the low ridges of the Urals into European Russia. The road is choked with lorry traffic and is a mess of brown salty snow and slush, creating endless visibility problems for me with my windscreen washer bottle having frozen solid weeks ago somewhere in Mongolia. The trip is however largely uneventful and I arrive without incident in Ufa, capital of the Bashkortostan Republic. I am hosted here by Alina and Milya, two beautiful, intelligent, English-speaking mixed Bashkir/Tatar sisters who live in the city with their mother. The Bashkirs and their neighbouring Tatars are the two dominant nations of a heterogeneous group of Kipchak nations, Turkic nomadic groups with both Caucasian and Mongoloid features who spread into the Ural and Volga regions in the 11th and 12th Centuries and subsequently became swept up in the Mongol and Turkic nations which made up the Golden Horde, led by Ögedei Khan, second son of Chnggis Khan, who invaded and conquered ancient Rus’ (the forebear of modern Russia) in 1237-40.

The Golden Horde subjugated Rus’ for almost 250 years, until a new generation of Russian tsars (ceasars) emerged following the breaking of the Tatar Yoke, with leaders such as Ivan IV (Ivan the Terrible) ruling over a new Russian Empire which began to reconquer lands inhabited by the various Kipchak groups. Despite merely extracting a tribute rather than being a fully occupying force, there was naturally a degree of inter-marriage between the occupiers and the natives of Rus’ and hence comes the expression ‘scratch a Russian and you’ll find a Tatar’. Today the Tatars are, after Slavs, the largest ethnic group in Russia and are well-integrated into Russian society, as demonstrated by Ufa, the vibrant and dynamic capital of the Bashkirs. Here there is not the atmosphere of racial animosity one finds in parts of the Caucasus, instead there is a more genuine blending of Tatar and modern Russian identities. Such is the extent of assimilation however that, despite concessions to national identity such as the Lala Tulpan (flowering tulip) mosque, the third-largest in Russia, one wonders how long an independent Tatar identity will survive in the modern Russian state before facing total assimilation, perhaps the ultimate reversal of the haunting Tatar Yoke which remains, deeply, in the Russian people’s collective psyche.

From Ufa I drive south-west towards the Volga, to the city of Samara which sits on a long, looping bend of the river, on its left bank. In the late sixteenth century Samara was established as an eastern border post of the Russian Empire and in the Soviet period, renamed as Kuybyshev, became a major industrial centre for the manufacture of aircraft and firearms. Today, despite being the country’s sixth largest city, Samara retains a slightly faded charm and comes as a pleasing surprise in a country where many western cities have been architecturally marred by bland and inconsistent modern architecture. The old centre, which spreads down to the sandy beaches of the Volga has a slightly untouched feel with Tsarist-era wooden houses with elaborately carved window frames, often showing a distinct lean and once grand apartment buildings in pastel shades of yellow, pink and green, decorated with often crumbling stucco architraves and balconies. The streets are lumpy, with the asphalt pushing up between the tram lines, and there is a general air of classy neglect.

Samara’s riverside setting also lends it a slight air of port-city seediness, with a long embankment running above sandy beaches packed with sunbathers in summer, past occasional clumps of trees and a number of ferry terminals from where boats depart on pleasure cruises. Across the river are the low Zhiguli Mountains, occupying the inner radius of the Samara Bend, a large loop in the Volga once famous as the redoubt of pirates who would prey upon river traffic. These mountains give their name to the ubiquitous Zhiguli car made in nearby Tolyatti, as well as the Zhigulevskoye Beer which was universally famous in the USSR and was first made here by an Austrian in the red-brick riverside brewery, where locals queue to buy beer in large plastic bottles and can even take river cruises from a dedicated brewery-jetty. Now, in mid-December the river is still unfrozen but the beaches and ferry terminals are quiet and there is only a gorgeous, deep-red sunset behind the smokestacks of nearby Novokuybyshevsk to admire. Samara, lacking the flimsy ostentation of many of the country’s more westerly cities feels authentically Russian, an easy-going, unpolished worker’s city, and quite possibly my favourite in Russia.

After four days in Samara I continue west and then north one afternoon, cutting out a large dog-leg in the Volga and driving via Syzran, Saransk and Arzamas through the night to arrive in Russia’s fifth-largest city, Nizhny Novgorod, one morning. Lying at the confluence of the Volga and Oka Rivers, Nizhny (Lower) Novgorod was newly-founded at the time of the Mongol invasion, and like Moscow and Tver manage to avoid destruction on account of its insignificance. As the medieval state of Rus’ slowly detached itself from the economically draining Tatar Yoke throughout the fifteenth century, Nizhny Novgorod served as a bulwark in the Russian expansion into the Khanate of Kazan, one of the successor-states of the Golden Horde. Later, in the crisis and chaos which followed the death of Ivan the Terrible in 1584 with no real successor (he had murdered his only intellectually-able son in a fit of rage) known in Russia as the Time of Troubles, it was from Nizhny Novgorod that Minin and Pozharsky rode to remove the Polish from Moscow, restoring the dignity of the nation once again and ultimately establish the Romanov Dynasty, which led Russia until the Bolshvik takeover in 1917.

At the centre of Nizhny Novgorod, as in many Russian cities, lies a kremlin (fortress), here one of the country’s oldest; a bulky, red-brick sixteenth century structure which seems to convey well the medieval power of the emerging state of Russia, and still houses the city administration. From the kremlin there are pleasant views over the Oka to the heavily industrialised right bank where during Soviet times, when the city was known as Gorky, the presence of military research and production facilities caused the city to be closed to outsiders. Outside the kremlin however, the city is thoroughly modernised and while by no means unpleasant, it lacks the antiquated charm of Samara.

It’s under 250 kilometres west from Nizhny Novgorod to the city of Vladimir, which marks my entry into the ancient heartland of medieval Russia, an area now known as the ‘Golden Ring’, and more traditionally as Zalesye (‘beyond the forest’) in Russian. Here lie the cities of the ancient principalities of Rus’, which defined the protoypal Russian state between the times of the earliest waves of Slavic migration from Kiev until the Mongol invasion. Vladimir is one of Russia’s oldest cities and together with the nearby town of Suzdal made up the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal, one of the successor states to Kievan Rus’ and the forerunner of the Grand Duchy of Muscovy, from which the modern Russian state was born. Vladimir is an unusually beautiful city set on a number of hills, separated by bare deciduous forest now dusted with fresh snow.

From this white landscape rise the famous White Monuments of Vladimir; the spectacular Dormition Cathedral with its golden domes so typical of Russian Orthodox architecture and the nearby Cathedral of St Demetrius, both masterpieces of the twelfth century, carved in fine white stone. St Demetrius is particularly eye-catching; a restrained, single-domed cross-Church with the simple, neat proportions and hemispherical dome heavily borrowed from the Byzantine Church architecture which apparently so awed the first Slavic envoys to Constantinople in the ninth century. The walls of St Demetrius are covered in beautiful stone carvings of saints performing miracles and of mythical animals, whose survival through the Mongol invasion, subsequently tumultuous history of Imperial Russia, and often callous destruction of the Soviets is most surprising. The cathedral is almost certainly the most beautiful building I have seen in Russia and must rank with the finest masterpieces of Armenia as one of the world’s finest pieces of Christian architecture.

I make a day-trip from Vladimir to the small nearby town of Suzdal which was part of various principalities during the early stages of Russian history, eventually joining the Grand Duchy of Muscovy (like nearby Vladimir) in the fourteenth century. Suzdal subsequently became something of a religious centre and remains packed with churches, cathedrals and monasteries, mostly from the eighteenth century and notable more for their sheer number and diversity of form and styles than for the beauty of any particular example; certainly there is nothing to compare to the cathedrals of Vladimir. It’s also something a tourist trap, quite unusual in a country where domestic tourism is rather under-developed, and foreign tourism hardly encouraged. Nevertheless on a cold weekday the number of tourists is modest and it’s very enjoyable to walk through the surrounding countryside, taking in the myriad examples of Russian religious architecture.

From Vladimir I continue west until I just enter Moscow Region, stopping in the town of Sergiev Posad which lies just off the outermost of Moscow’s five concentric orbital roads. Sergiev Posad (posad referring to a usually fortified settlement attached to a kremlin or monastery) is famous for the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, today the most important Russian monastery and home of the Russian Orthodox Church. Built initially in the fourteenth century, then rebuilt during the fifteenth century following destruction in a Tatar raid, the lavra (a type of monastery complex) was patronised by Ivan the Terrible who heavily fortified it in the sixteenth century as part of the defences of Moscow. The grounds of the lavra throng with pilgrims and visitors who come to see the relics of St. Sergius of Radonezh, the ancient painted icons and take away bottles of holy water. Architecturally it is an impressive fortified complex, marked by its soaring baroque bell-tower and the iconic blue onion domes, painted with golden stars, of the Assumption Cathedral. This gaudiness combined with the fervour of the pilgrims seems to have as much in common with the dazzling, colourful faïence and ritualistic shrine-worshipping of the Islamic cultures of the east, as it does with the grey and restrained Protestant rite of much of Western Europe. After years of Soviet repression, the Russian Orthodox Church has made a considerable comeback, with its higher members closely linked to the Russian government and priests all-too-often mimicking the new Russian business-class, conveying themselves in black SUVs with blacked-out windows.

Not wishing to get any closer to Moscow I make my way anti-clockwise around the city, through Dmitrov and Klin (where Tchaikovsky spent his final years) on terrible roads lined with spun-off vehicles, onto the M10 Highway which links Moscow to Saint Petersburg. I stop for the night in the city of Tver, another once powerful principality in Medieval Russia, only to be eclipsed in importance by Moscow like Nizhniy Novgorod or Vladimir. The Soviet period robbed Tver of the last of its remaining ancient monuments, though the distinctly faded travelling palace of Catherine the Great remains, harking back to a time in Imperial Russia when Tver was a rest-stop on the road between the two great cities. Tver is also the final city on my route which lies on the Volga, whose source is around 150 kilometres away to the west. Here the Volga, already almost two hundred metres across, has frozen solid, allowing me to walk across the surface of Europe’s largest river, just a week after leaving Samara where it was still completely open.

Beyond Tver I continue on the M10, covered in snow and packed with impatient lorries whose drivers take particular exception to my self-imposed speed limit of fifty kilometres per hour. One flings a plastic bottle at me as he passes, another sounds his horn angrily while overtaking, though I see him crashed head-first into the forest soon after. This endless carnage of twisted wreckage, the long hours of intense concentration and the constant proximity to disaster are starting to show on my nerves, and driving becomes rather wearisome. In one small town a policeman stops me and holds out his radar-gun, showing a reading of eighty-one kilometres per hour. My incredulous laughter seems to immediately dampen his hopes of a pay-off, and I continue my fifty kilometre per hour journey north.

My destination is the city of Veliky Novgorod, the most historic city in Russia proper. It was in this region that Russian civilisation began; where the earliest Eastern Slavic state emerged from an area populated by tribes of Slavic and Finnic / Uralic people. While the precise events of the Russian foundation myth are lost in semi-legendary and sometimes controversial histories, the balance of evidence suggests that a ruling class of Varangian (Viking) origin established the earliest settlements of Rus’, led by a cheiftan known as Rurik who quickly assimilated the customs and language of the native Eastern Slavs, and whose successor Oleg of Novgorod went on to found Kievan Rus’, the cultural foundation-stone of modern Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The original settlement in the region was known as Holmgard, which was superseded by nearby Novgorod, thus explaining why the name of Russia’s oldest city ironically means ‘New City’. In 1136, when Kievan Rus’ was in decline, the city-state known as the Novgorod Republic was established, stretching from modern-day Estonia to the Urals and constituting one of medieval Europe’s largest states. Novgorod also survived the Mongols, but would eventually lose its power when absorbed into the Grand Duchy of Muscovy in 1478 by Ivan III, forever to live in Moscow’s shadow.

Novgorod is a beautiful city, in some ways one of the nicest in Russia, filled with ancient monuments to attest to its long history. Particularly striking is the central Kremlin dating from the late fifteenth century and very finely executed in red brick, my favourite kremlin in the country. Within the Kremlin is the Cathedral of St. Sophia, burial place of Yaroslav the Wise, a leader of the principalities of both Novgorod and Kievan Rus’ dating from the mid-eleventh century, making it the oldest Russian Orthodox Church in the country. Also within the kremlin are Russia’s oldest palace, bell-tower and clock tower, and a huge bronze sculpture dating from 1862 and known as the ‘Millenium of Russia’, which glorifies a thousand years of Russian history. Opposite the kremlin, beyond its moat and a small forested park is the city’s modern central square and a huge, imposing Soviet regional administration building, adding an example of Soviet gigantism to the catalogue of Russian architectural styles.

Despite all its historical appeal, it is in Novgorod that I start to feel in earnest the insidious approach of Western Europe, with dull, imposed order replacing the natural spontaneity and disorder of life, over-manicured spaces taking the place of the endless wilderness intrinsic to much of Russia. The buildings have been restored to perfection and there is a touch of soullessness which rather negates what could be a highly atmospheric city.

My next and final destination in Russia is perhaps the country’s most celebrated city, the physical embodiment of Russia’s western, European face. The unsettled period of Russian history known as the ‘Time of Troubles’ ended with the establishment of the Romanov Empire in 1616, a dynasty who would rule the country for 301 years, transforming it into a vast empire even larger than today’s Russia, building the Russian economy with the introduction of serfdom which bound the previously wandering peasants to their landowners for life, thus greatly increasing agricultural output. Perhaps the most important scion of the Romanovs, and one of the few uncontroversially great rulers in Russian history was Peter the Great, a driven and ambitious young king who was captivated by the West and by the people and ideas of the Enlightenment. Peter was particularly obsessed by shipbuilding and the idea of naval power, and devoted immense resources to the establishment of year-round ports on the Black Sea and the Baltic. Employing the kind of ruthless militarism which permeates Russian history, Peter seized a swathe of the Baltic Coast from Sweden during the Great Northern War and built his own capital from scratch: Saint Petersburg.

Saint Petersburg, Russia’s so-called ‘window to the west’ is unique among Russian cities; an elegant and harmonious imperial capital poised on the Baltic and looking outwards towards the wider world. Peter the Great was the first monarch to leave Russia, and true to Russian style, his extravagant capital was built to be larger and grander than anything in Western Europe, including Versailles. The city would become synonymous with the Romanovs, and only lost its status as capital in 1917 when Lenin returned from exile in Finland and led the Red Guards in the October Revolution, soon having the entire Romanov family murdered, and moving the capital back to Moscow. Nevertheless, Saint Petersburg remains in many ways Russia’s cultural capital and is a far more appealing city than the dismal sprawl of Moscow.

As I drive into Saint Petersburg late in the evening, a city different from any other in Russia emerges with tall, long avenues of Baroque buildings instead of the standard Soviet apartment blocks, built in long, continuous rows set aside wide, gently curving roads and elegant canals. Immediately I feel a slight atmosphere of iniquity, a touch of fallen empire, a city with plenty of character. My hosts Alexei and Ksenya live in the very heart of Saint Petersburg, alongside Griboyedova Canal, very close to the location of the old woman’s house in Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. From the exterior, the apartment building is a fine example of faded grandeur, damp-looking and raffishly unkempt, but the interior is comfortable and modern with high ceilings and in all likelihood better build-quality than the elsewhere ubiquitous Soviet apartment buildings. Alexei and I step out into the street together the next morning; him cursing the the mayor for not clearing the knee-high mounds of filthy snow from the streets, and me cursing the appalling cold. Despite being just -11ºC, the damp air from the Baltic is truly numbing and feels far colder than -25ºC in dry, continental Siberia.

With only a few days to spend in the city I limit myself to an overview of the centre; passing the imposing Baroque Vorontsov Palace, now the Museum of Russia; onto Nevsky Prospect, named after Alexander Nevsky, a Grand Prince (later saint) of ancient Rus’; looking down the far end of Griboyedova Canal to the slightly gaudy Church of the Saviour on Spilled Blood, named for and built on the site of the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. Turning north I cross the Neva River, looking back to a magnificent view across a frigid expanse of wind-sculpted snow and ice to the vast Winter Palace and Hermitage, seat of the Romanov Tsars and Tsarinas. The damp, bitterly cold wind makes the waterfront almost unbearable and together with the short, dark days where the sun hardly seems to climb above the rooftops, I decide that Saint Petersburg would better be visited one summer in the future, and I am soon ready to leave.

I leave Alexei and Ksenya one morning, ready to drive the very final stretch of my trip across Russia to the Estonian border. Shortly after starting however, in the middle of rush-hour traffic, the truck starts to splutter and lose power as if it is running out of fuel, then finally comes to a halt. In over 120,000 kilometres of often rough travel during the last three and a half years, this is the first time it has ever stopped. After trying in vain to locate the problem, I tie a rope to the front of the truck and wave it at passing traffic. Within minutes a van driver stops, tows me several kilometres across the city, helps me get the truck off the road and then refuses even the suggestion of payment. Saint Petersburg may be an outwardly Western city, but this single experience demonstrates that here, the spirit of the Russian people which so sets them apart from Westerners is clearly still present.

Despite having my faith in humanity confirmed, I am still left with the prospect of an immobile truck, and after a little more diagnosis, some beer-drinking and a little anxious thought, I suspect that my fuel has started to gel and has blocked the strainer in the fuel tank. My solution is Russian; to burn Alexei’s petrol stove under the fuel tank in order to melt the wax. It is whilst watching the roaring stove under the tank that I notice the real cause of my breakdown; a long, aftermarket copper brake pipe which has been poorly fitted by a previous owner has somehow fouled on the rubber fuel hose and starved the engine of fuel. I straighten the kink and am utterly delighted when the truck fires straight back to life.

Two days later than intended I leave Russia’s second city and drive the final 160 kilometres to Ivangorod, a Russian fortress established in the late-fifteenth century by Ivan III which has at times been part of Sweden and later Estonia. Across the Narva River is modern-Estonia and a beast perhaps more daunting than the Russian Winter: The European Union.

Hello there.

You may recall we chatted via the Thorn Tree late last year. I’m Mike from Perth Australia and will be (inshallah as they say) backpacking in Russia in May if Mr Putin gives me a visa. (Waiting for passport to be returned). I am finalising my plans and appreciate you drive whereas I backpack/bus/train/hitch even. Can I email you some thoughts about my 30 day itinerary through the Caucauses, to Astrakhan and the delta area, up Volga to Stalingrad then to west Siberia (following the route of the Romanov’s) and if time permits up to Arcangel. Would love to get your views. If so please send me an email and I’ll seek your wisdom. Got to say the photos you took seem wonderful. This will be my second trip but this time getting off the beaten track a bit. And by the way where are you based?

I leave end of Feb to backpack Slovakia to Moldova and serbia, ticking off the last eastern Europen countries. Then meet the wife in Rome in April for some boring places – well that’s unfair it’ll be Malta and Tunisia- then back by myself to do the Motherland!!

Kind regards from Perth

Mike

Hi Mike

Thanks for your comments, good to hear from you again. I’ve sent you an email.

Regards

EO

Hi,

Came across your blog while researching my upcoming trip to SPB and Moscow in 2 weeks…. Many people write about the places they have visited or the people they have seen, but very rarely do they manage to evoke the romance, beauty and soul of it they way you have.

If you haven’t already, I hope you write a book one day. You’d have your first reader right here, I promise!

Will hope to carry your words with you as I travel.

– Rhea

Hi Rhea

Thank you very much indeed for such a kind comment; I am very glad that you enjoyed the article. I haven’t given much thought to a book concept over and above this website’s content, though I would never rule it out. In the short-term I will be concentrating on bringing the website up to date. Stages 27 and onwards should appear during the second half of this year onwards 🙂

I wish you all the best in your Russia trip; I hope you find it as fascinating and beautiful as I do.

Best wishes

EO

Helloa,

Yes, I hope to see the beginning of summer and all the colours in St. Petersburg especially… I shall look out for the next stages of your travel, and if you’re in India again some time (especially Bombay), do give me a shout if you need assistance!

Cheers,

Rhea