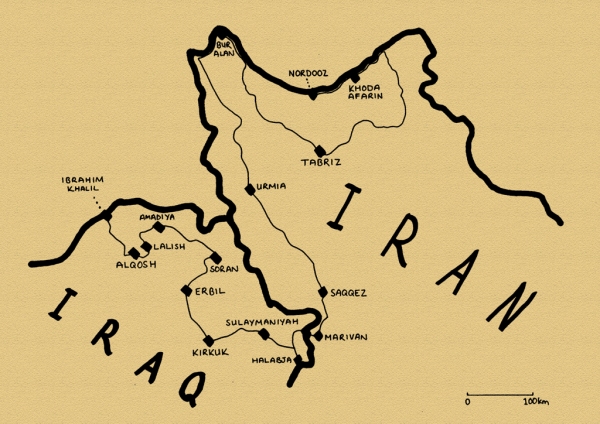

Stage 39 – Iran & Iraq: Kurdistan And Assyria

The rugged Zagros Mountains of north-western Iran and northern Iraq are part of the greater region of Kurdistan, homeland of the Kurds. Whilst in Iran the Kurds are a marginalised minority, in Iraq the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) controls a swathe of Iraqi territory autonomous from the Baghdad government which has remained peaceful and secure whilst much of the rest of the country has descended into chaos following the 2003 US-led invasion. Historically, these mountains on the northern fringes of Mesopotamia have been at the heart of Assyria, the ancient empire of the indigenous Assyrian people, one of the world’s earliest civilisations. Today the Assyrians are a minority whose religious distinction as Christians in an overwhelmingly Muslim region sees their renewed persecution from the barbaric actions of ISIL, who present an existential threat to the descendants of a culture which dates back perhaps as far as the twenty fifth century BCE.

It has long been a dream of mine to visit Iraq, but due to security issues and visa restrictions, much of the country remains off limits. In June 2014 however, the Peshmerga (Kurdish security forces) had seized control of the city of Kirkuk, an oil-rich city long fought over by its Kurdish, Turkmen and Arab inhabitants, giving me the opportunity to visit a large Iraqi city beyond the usual borders of the autonomous Kurdistan region.

Whilst the region has some beautiful scenery, it would be the surprising cultural diversity that made the strongest impression upon me; a patchwork of nations including Kurds, Assyrians, Yazidis, Turkmens and Arabs. The people I met would welcome me with extraordinary generosity and often share deeply profound experiences of life in this troubled region, against a backdrop of nearby war and humanitarian crisis. It would be an unforgettable insight into modern-day Kurdistan and Assyria.

In the afternoon of the 4th October 2014, I cross the Aras River from Armenia into Iran at Nordooz. I have a strange sense of detachment as I drive down-river along the Aras on the calm Iranian side, seeing first the barricaded border between Azerbaijan and Armenia, then the transition from populated Armenia to the destruction and abandonment of Nagorno Karabakh. I camp near the roadside overlooking the river and the depopulated territory I had been driving through two days earlier. Not a single light breaks the darkness. In the morning I continue, passing the beautiful bridges at Khoda Afarin; one dating from the twelfth century, now a beautiful ruin and a later, thirteenth century bridge with fifteen stone arches which is intact but sealed off with barbed wire. On the far side lie the ruins of a village and no sign of life. I pass two more modern bridges on my way downstream until, just before the town of Aslanduz, I have an intriguing view from a hillside down to the distant trenches of the front-line, where Armenia and Azerbaijan face each other across abandoned farmland.

I stop with a friend in the city of Tabriz which shines in the clear late-summer sun against a backdrop of flame-red hills. On the one hand it’s nice to be back in Iran, in a large, culturally rich and well-functioning country; on the other hand I am starting to tire of it; the oppressive uniformity of modern life, the terrible standard of driving and the feeling of a population whose freedom of expression is repressed by theocratic rule. It’s time to move on.

I leave Tabriz heading north-west, wishing to take a final look at Mount Ararat before I leave the region. It’s after dark when I re-join the Aras River at Poldasht and drive up toward the extreme north-western point of Iran at Bur Alan where I camp amid volcanic boulders. I wake at dawn to a magnificent view of Ararat’s twin peaks, wreathed in wisps of morning cloud under a full moon. Continuing on a road which winds through fantastic recent lava forms that look like giant sheep droppings, I pass an army post at Bur Alan. It looks like somewhere I shouldn’t be but I pass unnoticed and start climbing up straight towards the peak of Lesser Ararat, looking back at views across four countries; Iran, Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan where the tooth-like volcanic plug of Ilhan Dağ stands as a distant sentinel in the morning haze.

I cross the flank of Lesser Ararat and drop down to the shabby town of Bazargan, Iran’s principal border crossing with Turkey and the point at which I first entered Iran, as a backpacker, more than eleven years ago. I spend the day driving south, partly retracing my route from last July, and by late afternoon I have reached the city of Urmia. I want to find a place to camp and so drive out to the town of Golmankhaneh; once a port on the shore of Lake Urmia, but now poised on the edge of the salt flats which are all that remains of the lake. Here starts a rather pathetic episode of Iranian xenophobia and paranoia; seeing that I am a foreigner, two local men retreat and call the police; I am held at a local sports club until the police arrive. I am quizzed by a dim policeman, then after searching the car and generally wasting time, I am escorted back to Urmia and released. Such hysterical encounters are my least favourite experience in Iran.

Urmia is an ancient city which may date back to Urartian times, but it is historically notable for its Christian population. Although depleted by the spill-over of the Armenian and Assyrian genocides from Ottoman Turkey in 1914, the city remains something of a centre of Christianity with communities belonging to the Assyrian (Chaldean) Catholic Church, Assyrian Church of the East, Assyrian Protestant Church and Armenian Orthodox Church. I spend a very pleasant morning strolling around Urmia, visiting the various churches. At the Catholic St Mary’s Cathedral I speak the caretaker who is keen to show me around and explains that despite many Christians having left Iran following the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the Christian community is free to observe all festivals and to use alcohol; only the supply of alcohol to, or the conversion of Muslims is forbidden.

Nearby, the St Mary’s Church, belonging to the Assyrian Church of the East, claims to be one of the world’s oldest churches, having been founded by three Zoroastrian Magi (the Three Wise Men) following the birth of Christ, on the site of an older Zoroastrian temple. The church looks modern from the exterior and the interior, which includes a stone-walled grotto-like shrine with a statue of the Virgin Mary looks equally recently restored, making such grandiose claims rather hard to believe in. Here however I meet an Assyrian congregation following their Friday-morning gathering and speak to Ugin, the English-speaking son of a priest who tells me that his family speak Syriac at home and who is one of a population of approximately five thousand Assyrians in Urmia. It’s interesting to meet someone who is ethnically and linguistically a direct descendant of one of the world’s oldest civilisations.

I leave Urmia in the afternoon and drive southward, past the tragic remains of Lake Urmia; desolate, white salt-flats as a backdrop to the agriculture which has caused the lake’s downfall by syphoning off water from the rivers that feed it. Beyond the southern edge of the former lake, the land rises as I climb towards the province of Kurdistan, dropping past the city of Saqqez where I camp for a night. As I drive deeper into Kurdistan the following day, the scenery becomes ever more rugged with craggy mountains, under which forests of chestnut and scrub-oak are dotted by donkey paths and occasional mud-topped footbridges over rushing torrents of mountain water. My final stop in Iran is the friendly city of Marivan, where Maciej and I had stayed for a night back in early February 2009 and which now, in late summer, seems far more inviting than the cold and slightly rough-feeling town I remember. I am hosted by Hiva, a local Kurd who immediately feels like an old friend and whose unseen mother prepares for us one delicious meal after another.

North-east of Marivan the road takes me past Lake Zeribar whose gleaming blue water backed by forested mountains almost gives it an air of Kashmir, and soon arrive at the Beshmaq border crossing. I pass through a throng of lorries, mostly transporting fuel, but after a short wait I’m stamped out of Iran with little fuss. The Iraqi side of the border is calm and very friendly and after paying a customs fee of around twenty US Dollars I’m on the road, thrilled to be in a new country and to finally be in Iraq, even if my entry stamp is only good for travel in areas administered by the Kurdistan Regional Government.

I’m driving through an area of beautiful rolling hills, now golden with dry grass but dotted with pine and oak trees. The road is in excellent condition and driving standards seem to be higher than in Iran. There are even men in high-visibility jackets collecting litter from the roadsides. I cross a low pass and enter a long, wide valley; a beautiful drive in the warm, late-afternoon light. I aim for the tell (settlement mound) of Bakr Awa which is one of hundreds which may be found in Iraq; millennia-old piles of the detritus of early human settlements, a reminder that one is in the cradle of civilisation. I try to camp near the tell but am moved on by locals, sighting security concerns, and so sleep in a ploughed field a few kilometres away, just out of sight of the nearby city of Halabja.

Halabja is a rather nondescript provincial city infamous for the 1988 Halabja Chemical Attack, which killed between 3200 and 5000 people and left many more injured. It is the most deadly chemical attack in history which targeted civilians. Carried out by Saddam Hussein and other members of his Ba’athist government during the last months of the Iran-Iraq War, the attack aimed to destroy Kurdish resistance against the Iraqi Army and was also part of the wider, genocidal Anfal Campaign, which aimed to ‘Arabise’ northern Iraq by eradicating Kurdish settlements.

I drive into Halabja in the morning and head straight to the Halabja Memorial Monument, a modern building in the shape of a gas plume from a chemical bomb, which houses a deeply moving museum complete with dioramas and photographs of the appalling scenes witnessed on the city’s streets on the 16th March 1988; scenes of whole families killed by gas, of lifeless, chemically-burned bodies; a city where life had been wiped out and time seemed to stand still. The attacks drew a muted international response at the time, as Western countries and especially the United States who were supporting Saddam in his fight against the Iranians, falsely blamed Iran for the atrocity.

There’s little else to see in Halabja and in the afternoon I make my way north again to the junction town of Said Saddiq, from where I turn west towards the regional capital, Sulaymaniyah.

Sulaymaniyah is a bustling city of bazaars; thoroughly modern and rapidly growing. It is my host Baderkhan however who makes my stay here truly memorable. Half Kurdish, half Arab, Baderkhan is one of the great-grandsons of Mahmud Barzanji, who led a number of uprisings against the British Mandate in Iraq and in 1922 pronounced himself King of the Kingdom of Kurdistan, based in Sulaymaniyah; the closest the Kurds have come to an independent state in recent history. I meet Baderkhan in his pharmacy shop and after a lunch of kebabs he shows me around the city’s thronging bazaars which, while lacking the ornate elegance of those in Iran, have every bit as diverse a collection of goods on sale. Money-changers sit at the street-side with many thousands of dollars of cash just placed on a low table. I see a local cinema which openly shows soft-porn. Alcohol is freely on sale and Baderkhan tells me it is customary to drive up into the hills above the city and drink in one’s car; though drink-driving is frowned upon on weekdays. Further up, couples engage in romantic trysts; all with no harassment from the police. Sulaymaniyah is clearly pretty liberal by regional standards and it’s a refreshing sense of freedom after the cloying religious-authoritarianism of Iran.

After exploring Sulaymaniyah’s bazaar, Baderkhan drives me around town in his brand new Toyota Landcruiser, and I glimpse the lives of the city’s liberal youth, who entertain themselves in bars and fast-food restaurants. I meet Shevan, a political science graduate who now works for the Kurdish security agency. Brought up in a secular family, he now claims to be Zoroastrian and is clearly pro-American. He tells me that the Americans have done a lot for the Iraqi Army, but that the Iraq’s failed to take advantage of their training. What’s the future for Iraq, I ask? “There is no solution for Iraq; the country will be at war forever”.

In the morning Baderkhan takes me to the infamous Amna Suraka (Red Prison) where Iraq’s secret security service, the Mukhabarat tortured and imprisoned members of the local population until it was stormed by Kurdish forces during the Gulf War in 1991. Outside the bullet-pocked building are tanks, armoured personnel carriers, artillery and trucks hastily abandoned by the Iraqi Army in 2003 when the Second Gulf War broke out. The prison is now a museum of the Anfal Campaign. After entering, we walk through the ‘Hall of Mirrors’; 4500 lights (representing the number of villages said to have been destroyed) illuminate 182,000 shards of broken mirror, which represent the death toll. I see that Baderkhan is visibly moved by this. Although he now lives a very comfortable life, his family were greatly affected by Anfal. Despite Baderkhan’s father being an Arab, the family decided to leave Baghdad in 1991 when the Americans invaded and came to Sulaymaniyah. When Saddam began to attack the Kurds he, his mother and sister were forced to flee across the mountains with thousands of others and lived in a refugee camp in Marivan, Iran. “I opened my eyes under a canvas tent” Baderkhan tells me, with damp eyes. Beyond the hall there are gruesome waxworks of prisoners undergoing torture, with the cells left as they were found in 1991. Finally there is an exhibition on Kurdish history and culture, including a life-size figure of Barzanji, Baderkhan’s great-grandfather, which he avoids making eye-contact with.

Sulaymaniyah’s archaeological museum contains tantalising artefacts of the Mesopotamian civilisations which were based south of the Zagros Mountains of Kurdistan; areas sadly beyond the limits allowed by my entry stamp. Amid various Sumerian tablets is an original bearing part of the Epic of Gilgamesh, perhaps the oldest surviving work of literature, written in cuneiform, an alphabet used for more than three thousand years in Mesopotamia. There are also Sumerian statues, Akkadian bronzes, ivory inlay-work from Nineveh and a balbal (menhir) from the Turkic-era. Seeing such artefacts whilst standing in Iraq only heightens my resolve to one day find a way to visit the south: ‘Real Iraq’.

On my last day in Sulaymaniyah, Baderkhan drives me up into the hills to the east and north of the city, through rolling countryside which still appears somewhat depopulated; the legacy of Anfal. A road leads up a beautiful valley to a steep cliff-side where local legends describe a cave where a common man lived with the kidnapped daughter of a noble. Qizqapan is actually a sixth century BCE rock-hewn tomb whose facade depicts two men facing each other over what appears to be a fire altar. There are other flourishes of pre-Zoroastrian iconography including what looks very much like a depiction of the Mazdanic God, Ahuramazda as well as two carved ionic columns. Who exactly the figures are is not known but the larger figure may be the Medean King Cyaxares who turned the Medean Empire into a regional power at the expense of the Neo-Assyrian Empire; part of a transition of regional power from Mesopotamia to Persia which continued into the modern age.

After lunch at an Italian buffet, it is time to part ways with Baderkhan, who has spent most of the last three days escorting me around his home-town and making what would have otherwise been a fairly unremarkable city into an unforgettable experience. We part as friends with me vowing to return one day to see the South.

My next destination is the city of Kirkuk. Not technically part of Iraqi Kurdistan, I am only able to visit the city since its peaceful takeover by the Peshmerga in June of this year, though there is no guarantee that I will be allowed through the checkpoint on the road from Sulaymaniyah. Kirkuk is a multi-ethnic city with Kurds, Arabs and Iraqi Turkmens (descendants of Ottoman Turks, not Central Asian Turkmen) making up the majority of the population and all vying for supremacy in the city and oil-rich region which surrounds it. With a history of inter-ethnic violence and several bombings in recent years, Kirkuk is a place which Kurds in Sulaymaniyah have advised me to steer clear of, but having made contact with Arshed, a local Kurd who will host me for two days, I have decided to take advantage of what might be the only chance I get to see ‘Real Iraq’ for quite a few years.

It’s well after dark as I slip unnoticed through the checkpoint into Kirkuk Governorate and soon I see the lights of Kirkuk sprawling on the plains beyond. I meet Arshed on the busy main road and he escorts me into the winding city streets where he lives with his parents. His family are extremely welcoming and immediately ply me with food, eaten on the floor in traditional style. Outside, warm air masses from Mesopotamia clash with cool air from the Zagros and create a magnificent storm with an intensity which Arshed’s family have never seen. I have a sense of primal excitement; of breaking new ground into a region unknown to me and very rarely visited by other travellers.

In the morning, Arshed takes me out to explore Kirkuk. We start in a Turkmen bakery eating kahi, syrup-soaked pastry and börek, meat-filled puff pastry while another violent storm turns the street outside into a torrent. Turkmen, Kurdish and Arab customers all patronise this obviously popular breakfast spot. Once the rain has subsided, we make our way to the city centre which is clustered around an ancient citadel. With chaotic traffic, pot-holed roads, long, frenetic bazaars and shocking amounts of litter on the streets and choking the foul-looking, reed-lined Khasa River, Kirkuk reminds me strongly of my old home in Hyderabad, Pakistan and seems a world away from the clean streets of Sulaymaniyah. I immediately like the place. We are joined by Arshed’s friend Mahmud and after a brief discussion with an initially reluctant security guard, we are allowed to freely wander around the citadel.

Kirkuk’s citadel is built on a tell thought to date from Assyrian times, and contains a number of intriguing buildings; a rather plain, twin-domed mausoleum attributed (not uniquely) to the Jewish prophet Daniel; the Ulu Camii with an ancient brick minaret, a Chaldean cathedral which has been comprehensively destroyed and a number of beautiful merchant’s houses which appear to have recently been restored, then left to decay once again. By far the most beautiful however is the squat, tower-like mausoleum of Buğday Khatun, a fifteenth century Aq Qoyunlu (Turkmen) princess; evidence of the long history of Iraq Turkmen who regard Kirkuk as their cultural capital. Arshed and Mahmud explain that under Saddam, the Citadel was deliberately destroyed in an attempt to ‘Arabise’ Kirkuk. As we finish our tour of the citadel at mid-day, we hear the city’s mosques come alive with the call to Friday prayer, followed by what sound like fiery sermons.

In the evening we meet Arshed’s cousin Diyar and drive to the edge of the city to get a distant view of the oil-fields which make Kirkuk such a strategic prize in northern Iraq. Back in the city we visit the Rahimawa Bazaar, eat excellent falafel and then retire to a street-side sheesha bar for a smoke, watching the locals grill fish on charcoal braziers. Perhaps fifty metres from the cafe is a distinctive pattern of ballistic damage to the road surface; evidence of a recent bomb attack. A little further down the road is the site where Diyar’s brother was killed by a stray bullet when the US Army shot dead an old man driving a pickup who failed to stop at a checkpoint. I’m once again struck at what raw lives people live here in Iraq, the damage done by years of oppression and war which belies their great generosity and friendliness, and how I, thankfully, have no personal experience with which to compare it. Exactly three years after I reach Kirkuk, the city would be taken back by the Iraqi Army and many Kurds, including Arshed and Mahmud, would feel compelled to leave for their own safety.

As I leave Kirkuk I see signs for destinations in the south which I dream of visiting; Baghdad, Mosul, Tikrit, but all are off-limits – not to mention extremely dangerous – for a foreigner to visit. I drive north, back towards Iraqi Kurdistan proper, entering Erbil Governorate after considerable questioning from a suspicious soldier at the highway checkpoint. Erbil may well be one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities and from afar its citadel, perched on a thirty-metre high tell which might be more than seven thousand years old, evokes some of the magic of Aleppo (my favourite city). On closer inspection however, it is but a shell with little of Aleppo’s charm, and the surrounding city is disappointingly bland and modern-looking. As well as being the seat of the KRG, Erbil is also the headquarters of the Assyrian Church of the East and in the district of Ankawa are two cathedrals, now tragically thronged by refugees displaced by ISIL from their homeland in the nearby Nineveh Plains. Nothing however really hints at the city’s great age, perhaps due to it having been a backwater of the Ottoman Empire for centuries, and after one day looking around I am ready to leave.

From Erbil I head north-east, back towards the mountains on the British-made Hamilton Road which winds up to the Iranian frontier. I however stop in the town of Soran; a bland modern settlement whose population is mostly made up of returned Kurdish refugees whose mountain villages have been destroyed during Anfal. I’m hosted here by Oliver, an erudite British expatriate teaching in the local university; a cherished opportunity to speak at length with a native English speaker passionate about the region. I spend a day driving around the local area which is in places dramatically beautiful. Just below Soran a side-road climbs steeply into the rugged mountains with magnificent views over the Hamilton Road and up the narrow cleft of the Rawanduz River, which looks like small, grassy Arizonan canyon. Climbing further to the east, there are more beautiful mountain landscapes, but once again the legacy of Anfal is clear; there is an odd feeling of depopulation and any villages one does come across are modern and charmless, marred by the sight of blue plastic tarpaulins.

I leave Soran heading northward along a ridge of dramatically uplifted rock, turning westwards and crossing a low pass to drop to the valley of the Great Zab River, a major tributary of the Tigris. It’s a beautiful drive, following the wide, muddy river upstream until it turns northward into Turkey, to the rugged and restive mountains south of Hakkari through which I had passed almost three months earlier. I imagine the green and inviting mountains to the north of the river to be the base of Kurdish guerillas who occasionally prey on the Turkish military.

Shortly after leaving the Great Zab, I reach the striking town of Amadiya. Situated on a flat-topped mountain which juts from the surrounding valley, Amadiya must long have been settled and was part of Assyria in the third millennium BCE. In addition to its location, the town is also attractive in its own right, unlike the typically bland, modern settlements around it. With neither significant traffic nor squalor in its narrow, ancient streets, it’s an attractive place to stroll for an afternoon, amid a friendly population of Assyrians and Kurds.

In the evening I continue towards the regional capital of Duhok but turn south just before reaching the city on a road which will lead down to the Nineveh Plains around the troubled city of Mosul. I’m a touch nervous about entering this region as ISIL are currently advancing ever closer, but it might be the last chance to witness the region’s indigenous, non-Muslim communities. I camp at a low pass just above the road and spend an uneasy night punctuated by the eerie flickering of an unseen gas-flare, the distant thumping of artillery fire and the nearby calling of jackals.

After a somewhat uneasy night I descend through beautiful, spine-like ridges of craggy hills, the last undulations which precede the hazy plains of Nineveh and Mesopotamia. Up a scrubby side valley of olive trees I reach the village of Lalish; sacred to followers of the Yazidi faith and home to its holiest shrine; that of the hermit and saint, Sheikh Adi.

The Yazidis are a small ethnic group similar to but arguably distinct from the Kurds who follow a somewhat mysterious and often misunderstood monotheistic religion. Yazidis believe that an indifferent God created a barren and violent Earth and placed it under the care of seven holy beings or angels, chief of whom was Melek Taus, the Peacock Angel. The likeness of Melek Taus to Iblis or Satan in the Islamic tradition has long-fuelled incorrect, sensational and offensive claims that Yazidis are ‘Devil Worshippers’.

For a people who are renowned for being secretive and strictly endogamous, and who have long been maligned and attacked by their neighbours, I am very warmly received in Lalish. After a brief talk with elders I am given an acolyte, Kovan, as a guide, and am told that I may visit all places and photograph whatever I wish. Pilgrims are milling around the shrine, some from the large Yazidi diaspora now resident in Europe (mostly Germany), others such as two Armenian-born Ukrainians who come from Yazidi communities in the Caucasus. Many however are refugees, whose camps line the road and surrounding hills; Yazidis from Sinjar who have been displaced by the savagery of ISIL from their homes around a holy mountain close to the Syrian border.

Kovan and I enter the shrine through a door with a richly carved pediment and relief of a large black serpent, and enter the sanctuary. Here are tombs said to belong to some of the seven Earthly Angels, and central columns are tied with various brightly coloured cloths – representing the colour brought to Earth by Melek Taus – in which pilgrims tie a votive knot, kiss it and touch it to their foreheads whilst saying a prayer. The room is filled with olive-oil lamps and I’m told that 366 wicks are burnt each day. Beyond the sanctuary is the plain grave of Sheikh Adi himself, an eleventh to twelfth century Sufi born in what is now Lebanon who is regarded by Yazidis to be the Earthly incarnation of Melek Taus, and whose grave pilgrims circumambulate in prayer. Elsewhere in the complex are tombs of other, lesser saints, the sacred warm spring of Zamzama, and a room containing ancient-looking amphorae filled with the locally produced olive oil used in the lamps.

I leave Lalish thankful for a fascinating glimpse of a people and religion previously unknown to me, but deeply troubled by the obvious peril which these people are currently facing. Descending further toward the plain, I enter the Assyrian heartland around Mosul and a region which is even closer to ISIL. Created by the chaos and power-vacuum brought to Iraq by the Americans and fuelled by their atrocities, ISIL have spread rapidly across the country in recent months and have unleashed unspeakable brutality against the non-Muslim communities of northern Iraq, effectively continuing policies long perpetrated by Saddam and the Ottomans during the twentieth century. With many Christian Assyrians having fled to Turkey and Europe I fear this could be a final opportunity to visit these ancient communities which are descended from one of the world’s oldest civilisations.

Just before dropping onto the plain, I take a track up to a point known as Khanis where the Gomel River emerges in a wide gorge from the mountains. This is the location of what might have been the world’s first aqueduct, built around the eighth century BCE in the Neo-Assyrian Empire to control the flow of water to cities such as Nineveh. Little remains today except for a damaged relief of King Sennacherib, the eighth-century BCE ruler of Assyria who oversaw the building of Nineveh and destruction of Babylon. Here, close to the edge of Mesopotamia is another taster of the riches of the South, but the sound of artillery fire last night are a clear reminder that now is not the time to visit.

Once on the plains, I’m initially concerned at how close the front-line might be; the situation is changing fast, but I estimate ISIL to be perhaps twenty kilometres away in the haze. I’m put at ease however once I see Turkish and Iranian lorries on the road. My final stop in Iraq is Alqosh, a town of Neo-Aramaic speaking Assyrians who follow the Chaldean Catholic Church, nestled at the foot of the mountains. Although Alqosh is under the control of the Peshmerga and Dwekh Nawsha, the Assyrian militia, ISIL came perilously close just two months ago, causing many of the town’s residents to flee. I make my way up into the hills above town, driving up a tight serpentine road to the seventh century Rabban Hormizd Monastery, a striking catholic hermitage which hangs from a mountainside and looks to be straight out of the Holy Lands. Although there are doors open and even lights left on, the monastery is eerily deserted and the narrow valley channels sounds in from the plain, making the distant artillery fire seem suddenly more urgent.

Returning to the town, I have a brief walk around and find myself in a picturesque cemetery, filled with small, pavilion-like graves with Syriac inscriptions. There’s a nice view over an ancient-looking jumble of boxy, stone-walled homes which cluster around a large monastery. Here I meet Fazel and Sevan, two locals who after initially questioning my reasons for visiting, soon invite me in for tea and fruit. Although many of the town’s residents have fled, some are beginning to return and Fazel is confident that the Kurdish and Assyrian forces can hold on to the town. It’s startling to think that this community is poised on the very edge; staring into the plains at potential genocide.

Alqosh’s old town consists of wandering, narrow streets running between beautiful stone houses; by far the nicest which I have seen so far in Iraq. There are ruins of an eight-hundred year-old synagogue of the Biblical prophet Nahum and indeed, with its Christian, Aramaic-speaking inhabitants, domed churches and occasional palm tree sprouting amongst the stone walls, Alqosh has to me a distinctly Biblical air about it. In better times Alqosh would be a wonderful place to linger, but the ongoing sounds of artillery fire persuade me to leave and make my way towards the Turkish border. Five kilometres beyond Alqosh I join the busy Mosul – Duhok Highway and breathe something of a sigh of relief. I can’t imagine what it must be like to live for months with such an imminent and nearby threat to one’s life, people and culture.

I bypass Duhok on an eight-lane motorway but get into a snarling bottleneck at Zakho, where I stop long enough just to change some money and fill up with diesel before entering Turkey. The formalities on the Iraqi side of the border are long and chaotic, mostly it seems due to my exiting from a different border crossing from that at which I had entered, and it’s well after dark by the time I approach Turkish Customs.

My trip across this region has far exceeded my expectations. I came to Iraqi Kurdistan imagining it to be much like Kurdish areas of Turkey and Iran; ruggedly beautiful but culturally bland. Instead I had an insight into a very ancient region on the fringes of Mesopotamia, glimpsed ancient cultures whose very history is being written by current events and heard first-hand accounts from the wonderful people of the region of their raw, often tragic recent history. I came expecting to bypass the historical gravitas of Mesopotamian Iraq, but realised that in this complex ethnic patchwork within the mountains and northern plains, I had very much seen the ‘Real Iraq’.